On 17 March 2003, US President George W. Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein and his sons to leave Iraq within 48 hours or face military action. Bush’s demand marked a pivotal moment in the lead-up to the Iraq War and reflected the Bush administration's determination to use force to remove Saddam Hussein from power.

When Saddam Hussein failed to meet the ultimatum deadline, a US-led coalition launched a massive military invasion of Iraq on 20 March 2003 despite strong opposition from UN member states and key US allies such as France and Germany. The Bush administration justified the invasion on the grounds that Iraq possessed weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and that Saddam’s regime was involved in terrorism and harbouring Al-Qaeda operatives – allegations which later proved to be false.

By 9 April, US forces had largely seized the capital Baghdad, marking the fall of the Iraqi regime. Only six weeks into the war, on 1 May, Bush delivered a victory speech aboard the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier, announcing the end of major combat operations in Iraq and declaring victory in the war. The speech was delivered in front of a large banner that read ‘Mission Accomplished’. Saddam was captured later that year in December and subsequently hanged in 2006.

The impact of the invasion and occupation, the legitimacy and legality of which has been widely contentious, was devastating for Iraq. Although the invasion was relatively quick, the US occupation and establishment of a viable democracy proved to be much more challenging.

In the ensuing years under occupation, Iraq witnessed a continued state of violence as various resistance groups formed to fight back against the American invaders. However, political disputes and the emergence of armed groups and terrorist organisations, including Iran-sponsored Shia militias, Al-Qaeda In Iraq – that never existed in the country prior to the US invasion – and later Daesh, meant that what was supposed to be a national resistance began to degenerate into sectarian strife. The instability caused by the invasion and the subsequent sectarian tensions created an environment in which these groups were able to flourish. Two decades of conflict and political instability have left the country’s infrastructure severely damaged, leading to widespread poverty and unemployment.

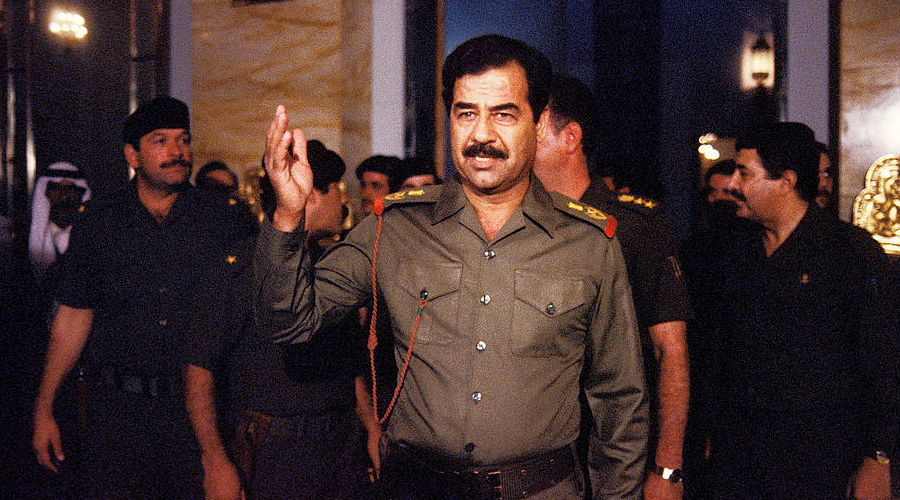

Iraq’s iron-fisted ruler

Saddam Hussein

During his reign, Saddam was known for his brutal grip on power. Government sanctioned torture, rape, enforced disappearances and executions were widespread. Even his family were not immune. As president he oversaw two major wars. In 1980, he waged a long and costly war with neighbouring Iran which lasted for eight years and resulted in hundreds of thousands of casualties on both sides. He also ordered the invasion of Kuwait in 1990, which led to the Gulf War and the imposition of international sanctions on Iraq.

Within Iraq, Saddam eradicated illiteracy, unemployment and poverty throughout the country, improved infrastructure, industry and the health care system and brought water and electricity to the remotest parts of the country.

Accused of human rights abuses, possessing weapons of mass destruction and harbouring terrorists, Hussein was the primary target of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. Following the invasion and the fall of Baghdad, he went into hiding but was eventually captured by US forces in December of that year. He was later put on trial and found guilty of crimes against humanity. He was executed by hanging on 30 December 2006, with the whole world watching the footage as a cloth was wrapped around his neck and he was led to the gallows.

With a contentious legacy, Saddam remains a controversial figure in the Middle East and beyond. While some view him as a strong and effective leader who developed Iraq and stood up to Western powers, others see him as a ruthless dictator who brought misery and suffering to the people of Iraq.

The Ba’ath Party

Under Saddam's leadership, the Ba’ath Party became the dominant political force in Iraq, entrenched in all aspects of Iraqi society, and he used it to consolidate his own power and suppress opposition. The party was known for its emphasis on Arab nationalism and socialism, with a strong focus on the need for Iraq to assert its regional influence and control its own resources. Despite the party's rhetoric of socialism and nationalism, Saddam's regime was notorious for its human rights abuses and repression of political dissent. Members of the Ba’ath Party were accused of being involved in torture, arbitrary arrests and extrajudicial killings.

The Ba’ath Party was dissolved following the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, and its members were banned from holding positions in the new Iraqi government. However, some former members of the party continued to play a role in Iraq's politics, including in the insurgency against US and coalition forces.

Faces of the Iraq war

In the lead-up to the invasion, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1441 in November 2002, which demanded that Iraq disarm its weapons of mass destruction and cooperate with UN weapons inspectors. The resolution did not, however, authorise the use of military force. Many member states, including France, Germany and Russia, expressed their opposition to the invasion, arguing that there was insufficient evidence to justify military action and called for a diplomatic resolution to the crisis.

The UN Secretary-General at the time, Kofi Annan, also expressed his opposition to the invasion, stating that it was not in compliance with the UN Charter and that the use of force should be a last resort. Despite these objections, the US and its allies pressed ahead with the invasion in March 2003 without the explicit authorisation of the Security Council.

While some perceived the invasion as a response to the 9/11 attacks, many saw it as a means of gaining control over Iraq's oil and global energy supplies. But for one group within the United States, the Neoconservatives, military action in Iraq was a vision of a new world order based on an aggressive and interventionist US foreign policy.

-

George Bush

-

Tony Blair

-

Ahmed Chalabi

-

Colin Powell

-

General Tommy Franks

-

Paul Bremer

-

Donald Rumsfeld

-

Condoleezza Rice

-

Ayad Allawi

The Iraqi army and rise of militias

After the fall of Saddam Hussein's regime, the US-led coalition embarked on a programme to rebuild the Iraqi military from scratch. This involved disbanding the entire Iraqi army and security apparatus, including the elite Republican Guard. The decision to disband the army, however, gave rise to insurgency and instability in Iraq. Not only did it leave many soldiers unemployed, but it also gave rise to militias that were formed by various groups and individuals, including former military officers, political parties and religious groups, and were often organised along tribal, ethnic, or sectarian lines. Many of these militias were initially formed to resist the US-led occupation, but they soon found themselves fighting against each other as well.

What does Iraq’s post-Saddam democracy look like?

Today, Iraq is a parliamentary democracy with a federal system of government that is based on a separation of powers between the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government. Iraq's current constitution, which was adopted in 2005, outlines the structure of the government and guarantees certain rights and freedoms to citizens.

The political situation in the war-torn country, however, is complicated by deep-seated ethno-sectarian divisions. The Muhasasa system, which has been in place since 2003, is a power-sharing arrangement based on ethno-sectarian quotas. It divides political power among the country's major ethno-sectarian groups: Shia Arab, Sunni Arab and Kurds - who are mostly Sunni. Under the Muhasasa system, the president is a Kurd, the prime minister is a Shia Arab, and the speaker of parliament is a Sunni Arab. Other key positions in the government, such as the heads of major ministries, are also allocated based on ethno-sectarian quotas.

The purpose of the system is to ensure that no single group dominates the government and to promote a degree of inclusivity in the political process. In reality, the Muhasasa system has led to deep polarisation between different communities in Iraq, with each group vying for a share of power and resources. This has fueled conflict and violence.

It also led to a degree of political stagnation and has been criticised for institutionalising sectarianism and perpetuating corruption and patronage networks, as parties and leaders often use their control of ministries and other state institutions to reward supporters and enrich themselves at the expense of the general public.

As the country continues to grapple with decades of political and economic dysfunction, the future of Iraq's political system remains uncertain and will depend in large part on the ability of the country's leaders to address these ongoing challenges and work toward a more inclusive and stable political system.

What happened to Iraq’s oil wealth?

Iraq is the second-largest crude oil producer in OPEC after Saudi Arabia. Yet despite the country’s vast oil wealth and significant revenues from crude oil exports, Iraq imports some 40 per cent of its gas from Iran and is still struggling to meet the basic energy needs of its residents. Severe shortages in power supply and energy have left many households with only a few hours of electricity per day and a lack of clean and hot water.

Twenty years since the war to ‘liberate Iraq’, the promise of a prosperous, oil-financed and democratic Iraq has yet to materialise. The legacy of the US-led war on Iraq has been characterised by political instability, sectarian violence, corruption and a failure to establish a sustainable and accountable government. While the 2003 invasion may have removed a dictator from power, the US-led reconstruction effort has failed to establish a transparent and accountable system, leaving Iraq struggling to rebuild and establish a functioning democracy.

For years since the US-led invasion, the lack of political stability and security not only devastated the country’s economy, infrastructure and social fabric but also meant Iraq was unable to attract significant foreign investment. This was exacerbated by the emergence of extremist groups such as Daesh. Iraqis, however, have been battling another perhaps more pervasive issue - corruption.

Corruption and mismanagement

In October 2022, a probe uncovered a staggering $2.5 billion of embezzled tax funds, in what was described as the ‘heist of the century’. The embezzlement case, which involves a network of senior officials, politicians and businesses, is only one of a number of major corruption scandals which made headlines in the country amidst estimates of nearly $320 billion lost to corruption from the state coffers in the 15 years after the Saddam era.

Officials and politicians in Iraq are often accused of syphoning off public funds and resources for personal gain, including oil revenues. From ghost salaries and ghost employees, to bribery and even oil smuggling, this rampant corruption which has plagued Iraq for decades has greatly reduced the amount of funds available for investment in the country’s inefficient energy sector, its infrastructure and economic development overall.

Despite being a major producer of crude oil - with exports in March 2022 bringing in a record $11.07 billion in revenue, the highest since 1972 - Iraq’s limited refining capacity and inadequate infrastructure have left the country reliant on the import of refined petroleum products to meet domestic demand, mainly from Iran.

Combined with poor governance and the absence of accountability, a lack of transparency has hindered the country’s ability to effectively manage the distribution of its oil wealth; leaving the public with little information on how oil revenues are being spent and how contracts are being awarded.

Ongoing disputes

The central government in Baghdad has also been seeking - and failing to assert its control over - some of the country's oil-rich regions, particularly in the Kurdish-controlled areas in the north.

While the majority of Iraq's oil wealth is located in the southern and southeastern regions of the country, where vast oil fields are located, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG)-controlled region in the north of Iraq is also home to significant oil reserves, estimated to be around 45 billion barrels. The KRG began exporting oil independently in 2014, in defiance of the central government in Baghdad, with the establishment of its own pipeline to Turkiye.

The Baghdad government, which manages and regulates the oil industry including the production and export of oil, opposed the KRG's independent oil exports, and the two sides engaged in a legal dispute over the matter. In February 2022, Federal Iraq’s Supreme Court ruled that the KRG’s production and export of oil and natural gas is unconstitutional and that all contracts between the KRG and international oil companies are illegal. The ruling was rejected by the KRG and the dispute remains.

Iraq's oil wealth remains a key driver of its economy, but the country faces serious challenges in addressing the significant gap between supply and demand and effectively managing and distributing its resources for the benefit of its citizens, whose daily lives are impacted by the lack of reliable energy, with businesses and schools forced to close during power cuts and many households resorting to generators or other alternative sources of power. Fueled by widespread dissatisfaction with the government's corruption, economic mismanagement and failure to provide basic services, a series of massive demonstrations erupted across Iraq in October 2019 demanding change.

Iraq has recently been looking less towards America and more towards China for the development of its energy sector, highlighted by the 2019 ‘oil for construction’ deal. In February 2023, the country signed deals with Emirati and Chinese companies to develop its gas and oil fields in a bid to become more self-sufficient and reduce dependence on Iranian imports. The government of Prime Minister Mohammed Al-Sudani has also announced the dismantling of the largest oil smuggling network in the Basra Governorate, which involves high-ranking officers and senior staff.

With an estimated 145 billion barrels of proven oil reserves and significant untapped oil resources, Iraq has the potential to address a lot of its deep-seated economic challenges. But one thing remains clear, effective governance and transparency are crucial if Iraq is to successfully capitalise on its oil wealth and direct it towards the development of the country to meet the needs and demands of its citizens and provide stability.

Frustration boils over: 2019 protests

Fueled by widespread dissatisfaction with the government's corruption, economic mismanagement and failure to provide basic services, a series of massive demonstrations erupted across Iraq in October 2019 demanding change. This was the biggest wave of anti-government protests in Iraq since the 2003 US-led invasion.

The protests were largely driven by young people, who have grown frustrated with a government they see as corrupt and ineffective. Demonstrators took to the streets in cities across the country, demanding political and economic reforms, better living conditions, and an end to government corruption and Iranian meddling in Iraqi affairs.

The protests were met with a heavy-handed response from Iraqi security forces, which violently cracked down on protesters, with the use of live ammunition and mass arrests. Hundreds of people were killed and thousands were injured over the course of the protests, which continued for several months until the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown measures.

Despite the government's efforts to quell the protests, demonstrators continued to demand change leading to the resignation of then-Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi in April 2020. Three years since the protests began, many of the protesters’ demands, including accountability for the killing of demonstrators in 2019, have not been met.

Accountability for the Iraq War

The Senate Report on Iraqi WMD Intelligence

The United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence published a report on 9 July 2004 examining the intelligence community's assessments of Iraq's weapons of mass destruction programmes leading up to the 2003 US-led invasion.

The report concluded that the Bush administration had exaggerated the threat posed by Iraq's WMD programmes to justify the invasion and that much of the intelligence was unreliable and had been presented to the public and policymakers in a misleading manner. It also found that the intelligence community had not adequately vetted the sources of the information on Iraq's WMDs, leading to significant errors in the intelligence assessments.

Several other congressional hearings and investigations were also conducted during and after the Iraq War, examining various aspects of the US government's decision-making and conduct before and during the Iraq War.

Commissioned by the US Congress and led by former Secretary of State James Baker and former Congressman Lee Hamilton, the Iraq Study Group Report was released in 2006. The report examined the overall strategy and conduct of the war and recommended a shift in strategy towards diplomatic and political solutions and a reduction in US military involvement. Other investigations include the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform's investigation into the use of intelligence in the lead-up to the war and the Senate Armed Services Committee's investigation into the treatment of detainees at Abu Ghraib prison.

The Chilcot Report

In July 2016, a public inquiry report which examined the UK's role in the Iraq War was published. The Iraq Inquiry was set up in 2009 to look at the decision making process which led to the invasion of Iraq and publish secret documents, including private communications from British Prime Minister Tony Blair to US President George W. Bush. It spans almost a decade of policy decisions between 2001 and 2009, examining geopolitical influences leading up to the war, the period of the war, as well as capturing the conflict's aftermath until 2009 when the inquiry was announced.

The inquiry heard evidence from a variety of witnesses, such as politicians including Tony Blair, senior civil servants, diplomats and high-ranking military officers. Although witnesses were not asked to testify under oath, they were asked to sign a declaration that their accounts were ‘full and truthful’.

The Inquiry was chaired by veteran civil servant Sir John Chilcot, who gave the report its name. The Inquiry found that the UK government, led by Tony Blair, had overstated the threat posed by Saddam Hussein and had not exhausted all peaceful alternatives before resorting to military action. The report also criticised the UK's post-war planning and lack of preparedness for the post-war period, which contributed to the instability and violence that followed. Ultimately, Chilcot concluded that the legal basis for the invasion was ‘far from satisfactory’ and that it was not a ‘last resort’, but the report failed to offer a verdict on whether the war was unlawful, on the grounds that the committee is not qualified to judge. Blair, who presented a ‘flawed’ case for war according to Chilcot, said he regretted the loss of life and the failure of intelligence services, but insisted the world is better off without Saddam.

The findings of the Chilcot Report had an impact on public opinion and political discourse in the UK. Many critics of the war saw it as a vindication of their opposition to the war and as evidence of the need for greater accountability and transparency in government decision-making. It also led to renewed calls for a more robust parliamentary oversight of foreign policy and military interventions.

Much like the US reports examining the US government’s decision-making, however, the Chilcot Report had limited legal impact. Though it was an admission of failure, deceit and misconduct, overall the report was seen as a trial with no verdict.

The legacy of the Iraq War

Two decades since the war to ‘liberate Iraq’, the Western promise of a prosperous, oil-financed and democratic Iraq has yet to materialise. The country has gone through significant upheaval since the 2003 US-led invasion. The war and its aftermath have had a profound impact on Iraq's society, economy and politics, and the country is still struggling with the legacy of the conflict.

Despite the toppling of Saddam Hussein's regime, Iraq has continued to face serious security challenges, including sectarian violence, insurgency, and terrorism. The rise of Daesh in 2014 was a major setback for the country, and the subsequent fight against the group took a heavy toll on Iraq and its people.

Iraq's political system has also been marked by instability and corruption, with a series of governments struggling to address the country's deep-seated problems. The 2019 protests highlighted the growing frustration of Iraq's youth with the country's political elite and the need for fundamental reforms. Economically, Iraq has struggled to rebuild and modernise since the war, despite having significant oil reserves. The country's infrastructure remains in poor condition and corruption and mismanagement have hindered foreign investment.

Twenty years on, it is clear that Iraq still has many challenges to overcome and that the legacy of the war will continue to shape the country's future for many more years to come.

Research and text: Jehan Alfarra

Videos: Jehan Alfarra, Usman Butt, Sulaiman Lkaderi, Alexander Morris, Sanja Skov

Development: MEMO's digital team